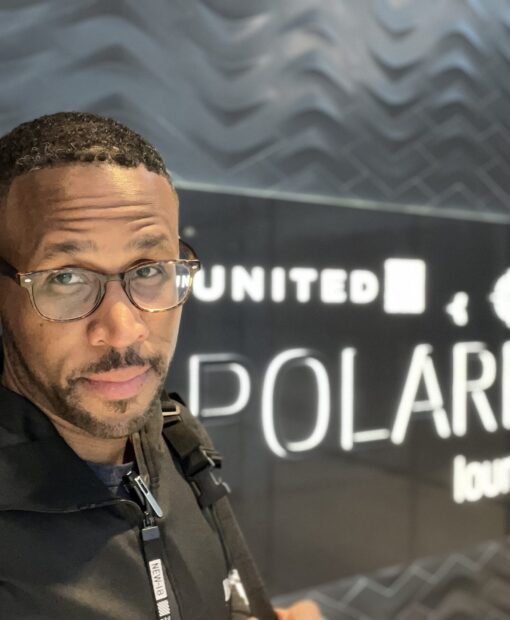

Dr. Idries discusses the day that he spent caring for displaced Syrian Refugees in Jordan’s Zaatari refugee camp. His day in the camp left him wondering “who said life was fair”?

Today was the day that I knew would be the most impactful, today was the day that I would go to the Zaatari refugee camp. The Zaatari refugee camp is located in Al Mafraq approximately 40 miles northeast of Amman and only 4 miles from the Syrian border. Zaatari was never designed to be a longterm solution and it’s current population of more than 80,000 people (camp was designed for a maximum of 60,000) are situated on a parcel of land measuring only 2 miles by 1.5 miles. Over the years, Zaatari has almost become a self contained city and with only rare exceptions the Jordanian government no longer allows residents to regularly leave it’s confines. There are 24 schools in Zaatari for the more than 25,000 children (meaning an average of 1,000 students per school). Thanks to many governmental agencies and NGOs there are multiple medical centers within the camp as well as food and sanitation facilities and services. Despite the basic services available to residents of Zaatari, services that other non-camp refugees can’t access, life there is by no means easy. Most homes consist of a small, single-room shipping container with corrugated metal roofs, all of the roads are un paved (making for a very dusty environment leading to tons of respiratory illnesses) and privacy is virtually nonexistent. Many of the residents have been in Zaatari for years and most of the children know no life before Zaatari. The residents of the camp have no idea when (or if) they will ever leave or if they will ever see their homeland again.

Like all the days before it, my day in Zaatari started bright and early. Early mornings, long clinical days and late nights visiting various refugee community centers around Amman produced an ever worsening exhaustion. Regardless, I woke up with an extra bit of anticipation because Zaatari embodied what this crisis and what this mission was all about. After our usual hotel group breakfast, we poured into the parking lot looking for our designated bus or van. Today I was in bus #2, the same yellow bus that days earlier carried me to Irbid.

The ride to Zaatari took a little over an hour as the density of central Amman quickly gave way to the dusty brown desert landscape of the Jordanian countryside. As the bus pulled up to the Zaatari military checkpoint our group leader reminded us that all photographic equipment had to be put away as photography is strictly prohibited at all checkpoints. Formalities completed, we slowly made our way into the camp, navigating its narrow dusty streets lined with small homes that were little more than shipping containers. Our buses (there were two on this day) quickly reached our bustling clinic and our day officially began. As we poured out of the bus and into the clinic waiting room I was a bit taken aback by the sheer volume of people waiting to see us. No matter I thought, we had a phenomenal team and we were going to remain there until every last patient was cared for. My interpreter and I were quickly directed to a small room with the sign above the door saying “Cardiology clinic”. That couldn’t be any further from the truth I thought as I walked in and started to setup.

My exam room was no more than 9 X 6 feet with a dusty sloping floor, a single exam table and a broken ultrasound machine that had to be from the 1980s. I was later informed that I actually had “the best room” because I had a window and a fan (both of which were much appreciated when the sun began to peak and the trailer began to swelter). I smiled as I glanced out of my window catching a glimpse of a cute little girl doing what cute little girls the world over do, playing and jumping in front of her home as her mom hung laundry. A closer look however revealed that her clothes were dirty and her feet were bare…..my smile quickly faded. Clearly this little girl was not like other little girls. She was a refugee trapped in a camp in a foreign country. Welcome to Zaatari!

My first patient was a middle aged woman from the Syrian town of Aleppo though she had been living in Zaatari for almost four years. Her medical complaint was pretty routine, her period was a few months late. Based upon her age, 46, I presumed that she was probably experiencing peri-menopause however any OB/GYN worth his or her salt will never exclude the possibility of pregnancy based strictly upon age (young or old). She certainly wouldn’t be the first 40-something who mistook an un-planned pregnancy for menopause. So through my interpreter I asked her,”is it possible that you could be pregnant?”, a question that my patient clearly found a bit humorous. With a quick burst of laughter she brushed this off as “absolutely impossible”. A few seconds passed and her demeanor quickly changed. She began to explain that her husband has been missing for the almost four years that she has been in Zaatari. He was taken from their home one night by what she could only assume were members of the Assad regime and he has never since been seen. This prompted she and her son (whom she feared would be taken next) to make plans to flee their home in the cover of darkness the following night. They unfortunately never got that chance she went on to explain. The following morning their neighborhood and their home were amongst many to be struck by barrel bombs. She was okay but her son was not nearly as lucky. Again a smile came to her face as she explained that her son did survive but just as quickly as it appeared the smile faded as she recounted the extent of his injuries. Her son is now paralyzed from mid-chest down but “Al-Hamdulillah (praise be to God) he is still alive” she ended. We all smiled and echoed her sentiments “Al-Hamdulillah”.

Our day in Zaatari was actually not nearly as busy as our previous days had been due to the rather extensive medical services various organizations provide Zaatari with. This means the demand is not as acute as it is in the outside communities. Having finished seeing patients by about 2PM, a few of my colleagues and I decided to explore the camp. I was immediately stricken by how this one place simultaneously embodied the worst and best of the human spirit. The worst is obvious. The Syrian crisis is a man-made crisis. Man created it, man perpetuates it and man ignores it. The fact that Zaatari even exists however is a testament to the best of the human spirit. Man cared enough to provide his fellow man with a safe haven, man continues to care enough to donate time, money and expertise to his fellow man though they have no direct relationship. We had the opportunity to speak with many of the residents of Zaatari both in the clinic and in the streets and we found a resilence and a hope that can only be described as being part of the best that the human spirit has to offer. There is undeniable anger and frustration but there is also undeniable optimism and hope.

Walking the narrow dusty roads of the camp, my colleagues and I were amazed by how much Zaatari resembled an otherwise normal city. Of course there are no high-rise buildings and the homes and businesses are shipping containers and trailers but in other ways the residents of Zaatari have produced some semblance of a normal life. The main shopping boulevard is ironically called the Champs Elysees (named after the famous 1.2 mile long boulevard in Paris) and we were amazed by the variety of goods and services available in the makeshift market. This shopping district was like any other in so much as people milled about the stores and went on with their daily activities. We were stopped by more than one group of young boys asking us our names and inquiring where we were from. There is a feeling of community in Zaatari and you have the sense that many here care about and look out for their brothers and sisters. Zaatari is nothing like their actual home, these residents have no choice but to be there and would like nothing more than to leave. Their spirits however still seem high and their hopes undeterred.

Our day in Zaatari came to an end all too quickly for me. As my colleagues and I waited for our buses, groups of children came to play and take pictures with us. We all shared our snacks with them, many of us shared some laughs and a few of us even shared hugs.

As our buses pulled away headed back down those same narrow dusty roads that brought us in that morning, I saw the gates ahead that for us were exit gates. I then caught a glimpse of the kids waving goodbye in the rear view mirror, for them these were one way entrance gates. The big smiles on their faces reminded me of my own five children who’s smiles I so terribly missed. Like a ton of bricks it hit me, these people are not just statistics or some faceless “others” only mentioned at the top of the international news hour. These people are not radicals, they are not terrorists and they are not dangerous. They are adults and they are children, they are human beings, they are mothers and fathers, sons and daughters, sisters and brothers. They. Are. People! I was lucky to be able to exit via those gates that day and all I could do was pray that soon these souls will also be able to see the EXIT gates of Zaatari through their rear-view mirror as their little yellow bus takes them to the start of the rest of their lives. It just didn’t seem fair but in Zaatari who said life was fair?

June 26, 2017

June 26, 2017

October 20, 2023

October 20, 2023