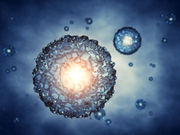

Embryo Development Put ‘On Hold’

Putting stem cells into hibernation during embryo development has potential implications for infertility, cancer, regenerative medicine

Embryo Development Put ‘On Hold’

Scientists from the University of California in San Francisco say that they were recently able to halt development of early mouse embryos for up to a month in the lab before the embryos then resumed normal growth. This research could prove important in areas such as assisted reproduction, regenerative medicine, aging and even cancer, according to the team from the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF).

The investigators used drugs that dampen the activity of a cell growth regulator called mTOR to put these early mouse embryos (blastocysts) into a stable and reversible state of suspended animation for up to four weeks. When no longer exposed to the mTOR inhibitors, the embryos quickly resumed normal growth and developed into healthy mice when implanted back into adult female mice, the study authors said.

“Normally, blastocysts only last a day or two, max, in the lab. But blastocysts treated with mTOR inhibitors could survive up to four weeks,” lead author Aydan Bulut-Karslioglu, said in a university news release. She’s a post-doctoral researcher in the lab of senior author Miguel Ramalho-Santos, an associate professor of obstetrics/gynecology and reproductive sciences at UCSF. The findings surprised the researchers, who launched the study to learn how mTOR-inhibiting drugs slow cell growth in blastocysts.

“It was completely surprising. We were standing around in the tissue culture room, scratching our heads, and saying wow, what do we make of this?” Ramalho-Santos said in the news release. “To put it in perspective, mouse pregnancies only last about 20 days, so the 30-day-old ‘paused’ embryos we were seeing would have been pups approaching weaning already if they’d been allowed to develop normally,” he explained. It may be possible to put mouse embryos in suspended animation for much longer than the four weeks achieved in this study, the researchers suggested.

“Our dormant blastocysts are eventually dying when they run out of some essential metabolite within them. If we could supply those limiting nutrients in the culture medium, we should be able to sustain them even longer. We just don’t know exactly what they need yet,” Bulut-Karslioglu explained.

This research could have a major impact in assisted reproduction for humans, which is currently limited by the rapid degradation of embryos once they reach the blastocyst stage. Being able to halt development of blastocysts may avoid the necessity of freezing embryos and give doctors more time to test fertilized blastocysts for genetic defects before implanting them, Bulut-Karslioglu suggested.

However, scientists note that studies in animals often fail to produce similar results in humans. The researchers also noted that mTOR inhibitors are already in clinical trials to treat certain forms of cancer, but these findings suggest a potential danger of this approach, according to Ramalho-Santos.

“Our results suggest that mTOR inhibitors may well slow cancer growth and shrink tumors, but could leave behind these dormant cancer stem cells that could go back to spreading after therapy is interrupted. You might use a second or third line of drugs specifically to kill off those remaining dormant cells,” he said.

The study was published online Nov. 23 in the journal Nature.

More information

The U.S. National Library of Medicine has more on fetal development.

— Robert Preidt

SOURCE: University of California, San Francisco, news release

November 24, 2016

November 24, 2016

May 19, 2018

May 19, 2018